Variety through contrasts

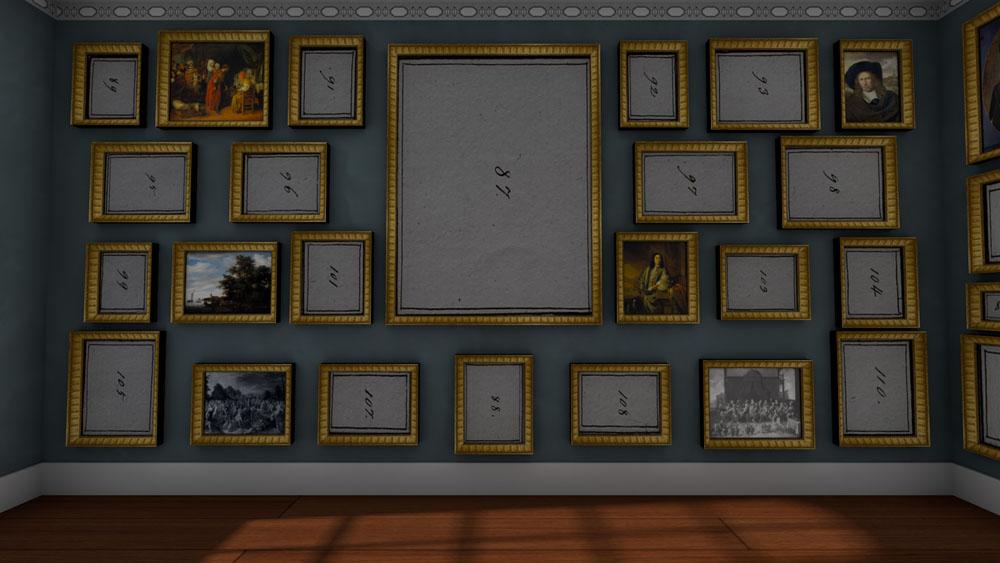

In the Room to the Right (“Chambre à droite”), Johann Friedrich Städel mainly showed – in this order – Dutch, Flemish, and Italian works. He divided the paintings symmetrically according to schools and subjects. Through their central position in the upper section of the wall, as well as through their dimensions, history pieces and portraits were clearly recognisable as the most prominent works. Comparable in terms of quantity were the landscapes, while only a few genre paintings, still lifes, naval pieces and vedute complemented the presentation.

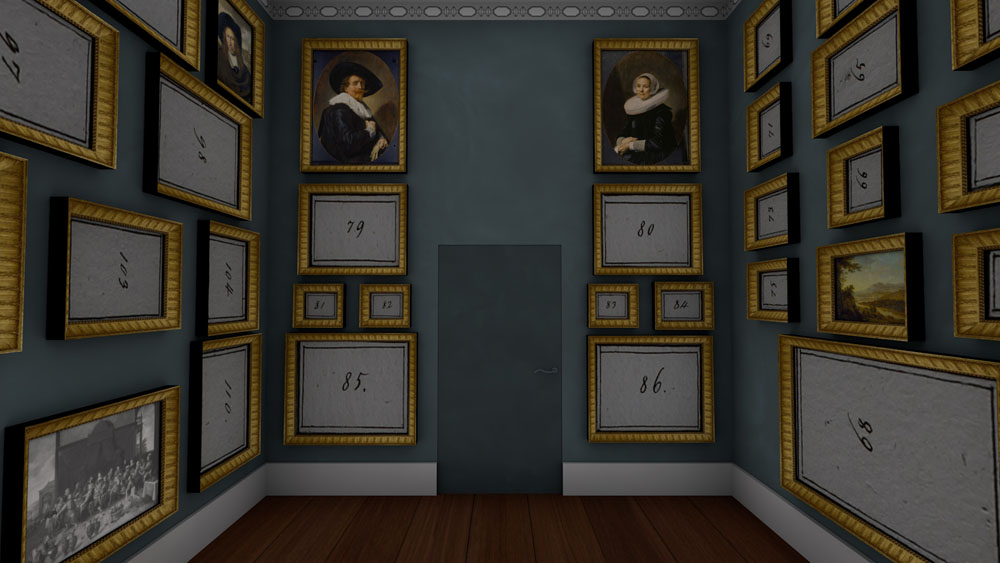

By combining similar motifs painted by stylistically diverging artists, Städel created a remarkable diversity: juxtaposed to the left of the entrance were two paintings of bearded older men, one attributed to the Venetian Giuseppe Nogari, the other to the Fleming Abraham Janssens, who had lived over a century earlier (inv.-no. 71 and 72). Hung above these works was a pair of paintings respectively showing a man and a woman looking upwards. One was regarded as a work by the Spanish master Jusepe Ribera, the other as a painting by the Italian Guido Reni (inv.-no. 69 and 70). On the west wall, the visitor would have been greeted by two impressive portraits of an unknown Dutch couple by Frans Hals. During Städel’s time, however, these were considered as portraits of Peter Paul Rubens and his wife (inv.-no. 77 and 78). A similarly prominent presentation of portraits could also be found in the exquisite collection of the Paris banker and collector Pierre Crozat (1661-1740) or in the likewise renowned Picture Gallery of Elector Johann-Wilhelm von Pfalz-Neuburg (1658-1716) in Düsseldorf, which would at a later point be moved to Munich.

The largest work in this room Städel had positioned in the centre of the longitudinal wall, opposite the entrance. The painting showed “Samson Battling the Philistines”. As it was sold by the museum already in 1834, and for a relatively small sum, it was likely not an original by the Venetian Baroque painter Andrea Celesti, but a copy. The other works, most of which had a landscape format, were symmetrically presented on both sides of the supposed Celesti. Landscapes were presented opposite landscapes. Yet, the rule was that Dutch landscapes would be contrasted with Italian ones. Daylight and night-time scenes or different seasons were combined as well. Städel’s contemporary Christian Ludwig von Hagedorn (1712-1780) illustrated this concept while describing his own collection:

“Remoteness over here, wilderness and a cave over there. A sunset in the Orient, shining through a forest, which, because of its red sky, promises wind and rain for the next day, has as its companion an image of a storm with figures wearing whirling coats who can scarcely withstand the wind and flying dust. I have all these different landscapes, seasons, hours and types of weather in my chamber.”