1833

Neue Mainzer Strasse

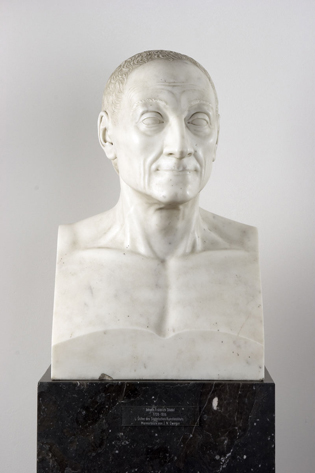

“Standing on both sides of the stairs are busts of Raphael and Dürer, as representatives of newer Art selected rather appropriately and agreeably.”

Located on the ground floor of the modified Vrints-von-Treuenfeld Palace were the art school and studio spaces. The main floor was reserved for the painting gallery, the extensive collection of plaster casts, as well as for the graphic collection and the library. Before entering, the visitor would pass both Raphael and Dürer.

At the time of the opening in March 1833, the still unfinished bust of Dürer was replaced by a plaster cast.

A tour

through the collection rooms

Floor plan

Reception rooms

From a “forecourt” in the stairwell on the first floor, the library could be accessed on the right, while the graphic collection was located on the left. Continuing straight on, the visitor would reach the three transverse reception rooms, also known as the “central rooms”. These served as “conversation rooms”, that is, for the entertaining of art lovers, but they were above all meant to prepare guests for the enjoyment of the artworks. Here, visitors could train their eyes, so that they would be able to make their own judgments on quality. The artistic standard was rigidly established: permanently exhibited here were engraved copies of works by Raphael and of antique paintings.

“When entering the Gallery, these three central rooms are meant to display the summit or perfection of Art, for a possible historical overview.”

Building a bridge from Antiquity to the present

From the reception rooms, one could look in two directions: adjacent on the north side were the skylight rooms with antiquities, while the painting gallery was located on the south side. The presentation of the artworks was programmatic. While the tract ended on the one side with a cast of the “Laocoön Group”, considered to be the epitome and unsurpassable highlight of antique art, the bust of the founder, Johann Friedrich Städel, constituted the endpoint of the tour. To reach it, visitors had to pass through the room with Dutch and Flemish paintings, the German room, and finally arrive at Italian painting as the culmination of artistic development. Placed here in a niche was Johann Nepomuk Zwerger’s idealised portrait bust of Städel, which did not by accident remind of both Roman examples and the busts of Raphael and Dürer in the stairwell.

[Städel’s bust is placed] “in such a manner that the founder of the institution, looking through all the rooms, can easily be recognised as the master of the house, and he on his part can, as it were, welcome the visitors and perambulators.”

A collection of casts

The strictly axial arrangement of the rooms allowed visitors to experience highlights of the development of antique sculpture in the northern section of the floor. Besides well-known single figures, casts of the Parthenon frieze of the Acropolis in Athens were presented in the first skylight room, while casts of the frieze of the Temple of Apollo at Bassae were presented in the second.

The collection of plaster casts of antique and – to a much lesser extent – Gothic and Renaissance sculptures had been systematically assembled from 1817 on. The reproductions, mainly ordered in Paris and London, were considered to be equal to the collection of original paintings and prints. Thus, the collection of casts did not only occupy a place of equal rank as the painting gallery at the Neue Mainzer Strasse, but also after the museum moved to its present location at the Schaumainkai. Only in 1907 were the casts removed by the then director of the Städel Museum, Georg Swarzenski (1876-1957). In accordance with the spirit of the times, he considered them to be nothing more than “art-scholarly study objects” that in no way could be compared to originals. The plaster casts were first put into storage and subsequently moved to Frankfurt University, founded in 1914. There they became part of the study collection of the Archaeological Institute. With the exception of the casts of the Parthenon frieze of the Acropolis, which had been firmly walled into the Institute’s former rooms in the Jügelhaus, the University’s original main building, all casts were destroyed in 1944 during the bombings of World War II.

Painting gallery

The sequence of the “painting rooms” in the southern part of the building reflected the artistic ranking of the time: a skylight room with seventeenth-century Dutch and Flemish paintings was followed by the “Early German” room. Here, numerous former altar panels from Frankfurt churches had been put on display. As a result of the Secularisation, these had been handed to the Frankfurt Museum Society after 1806 and were occasionally presented at the Städel. The Italian room constituted the highlight and culmination of this sequence. The wing facing the garden accommodated less significant works, among which numerous Dutch and Flemish paintings in the first room, but also works by predominantly eighteenth-century Frankfurt artists in the third room.

Contemporaries

For practical reasons, the chronological sequence of the rooms was interrupted in the southern wing. For examples of the latest contemporary art, larger surfaces were required: in the second room of the wing, cartoons by Nazarene artists such as Friedrich Overbeck and Philipp Veit were exhibited. In 1833, the larger room to the south was still closed. After 1835, Veit would paint his fresco representing “Christianity Introducing the Arts in Germany” on the longitudinal wall opposite the windows. With this work, the new leading medium of mural painting, which had previously only been practiced in Rome and Munich, was introduced in Frankfurt. The fresco symbolically expressed the Nazarenes’ claim as the innovators of German art, as heirs of Raphael. At the same time, it constituted an example of the technique of fresco painting, which could be studied and tried out by the budding artists at the Städel School.

Philipp Veit’s studio spaces were located on the ground floor of the wing. A small stairwell connected these directly to the collection rooms on the first floor, as well as to additional “practice spaces with northern light” on the second floor (Board Report 1936, p. 6). The back section of the wing could therefore be considered the “hotspot” of contemporary art: a fourth room (probably located on the axis of the exhibition rooms) was used for the display of new acquisitions, while the fifth room was later possibly used by the “Kunstverein” (“Art Society”).

Experienced

art history

In the exhibition rooms, the history of art was staged according to the ideas of the nineteenth century. Even if one had to take the peculiarities of a gradually expanded collection into account, the design and presentation of the rooms followed an internal logic that was intended to convey a clear perception of a development in art: Raphael was not just the centre from a spatial point of view – through the engraved copies of his Vatican frescos permanently on display in the reception rooms –, they also served as the perfect artistic benchmark. His art was viewed with classicist eyes, despite the fact that the coloured engravings after the frescos in the Loggias and Stanze were produced during the late eighteenth century. Represented in this manner, the Italian Renaissance constituted the filter through which one had to regard antique, as well as modern and then contemporary art.

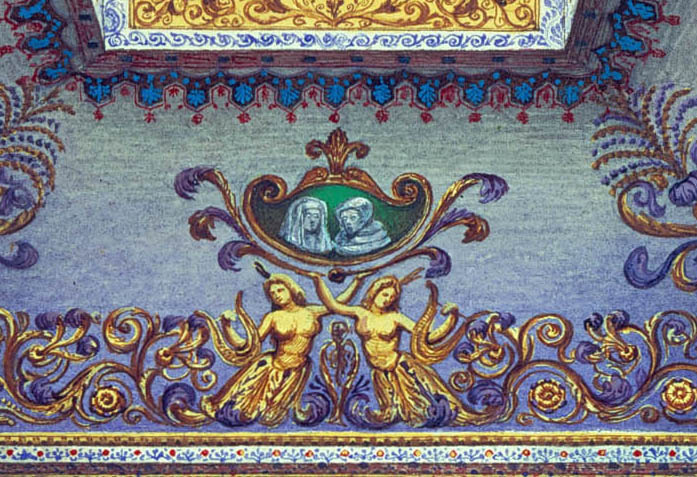

The rooms were furnished with different wall colours and ornamental decoration. These were intended to bring the visitor in the mood of the respective time, as well as familiarise them with the foremost artists of the period. The figurative images, based on designs by Philipp Veit, in particular expressed a specific view of art history.

Veit’s pictorial programme provided an interpretation of the museum’s presentation on an art-historical level. His thesis was that art cannot exist without religion. This notion was already to be instilled upon the visitors in the stairwell. Here, Veit had planned scenes based on the stories of the feasts for Hephaestus, the Greek blacksmith and patron of the arts. “The Torch Relay”, however, was never executed.

Greek origins

In the first skylight room with antiquities, the question concerning the origins of art was asked. Colourwise reduced to the “style of Greek vase painting”, the images were dedicated to divine and human artistry, as well as human creativity: Hephaestus as a blacksmith, Prometheus as the creator of mankind, Penelope as a weaver, and Daedalus as inventor.

A German Renaissance

In the painting gallery, only the middle room, dedicated to Early German painting, was decorated with allegorical mural paintings. Historically, these were related to the (German) Middle Ages. Over the entrance to the Italian room (and therefore in the line of sight of the founder’s bust), one could see “The Harmony of the Three Arts”, these being Architecture, Sculpture and Painting. Above the opposite entrance, the “Awakening of Art” under the influence of religion was depicted. The topic specifically related to a German Renaissance.

Although the images on the ceiling had been painted on paper by Veit’s studio assistants, they were intended to imitate mural painting. For one critic, their realisation stood in stark contrast to their content:

“Was there a lack of money? […] Not without mournful feelings I walked around in this hall for a long time and was quite upset about the wealthy citizens of Frankfurt.

– Paper-backed wall papers – watercolours – gold foil. Oh, Venice! Oh, Rome!”

Catholic and conservative

Following his mother Dorothea and his stepfather Friedrich Schlegel, the painter Philipp Veit had converted to Catholicism. As with many Nazarenes and Romantics, it was self-evident to him that “religion”, as bearer of all forms of culture, was synonymous with the Roman-Catholic Church in the medieval tradition. This notion was supposed to be visualised in a programmatic mural image in a gallery room intended for medieval and modern sculpture, adjacent to the Italian room. However, Veit’s initial design for “Christianity Introducing the Arts in Germany” was refused by the Board. It had too strongly emphasised the role of the catholic clergy.

The work in its entirety was designed like a triptych. Similar to the way the busts of the Roman artist Raphael and the Nuremberg master Dürer were placed at the entrance of the collection, the personifications of Italia and Germania were depicted opposite each other on the left and right “wings”. They represented Antiquity and the Middle Ages but also clerical and worldly power, papacy and emperorship. During the time of the “Vormärz” (“pre-March”), this idealisation was also the expression of a conservative political direction. Frankfurt played an important role in this context: in the left background, the city’s silhouette borders directly on that of Rome; for centuries, the self-image of the Free Imperial City had been strongly linked to the imperial elections and coronations.

Mary Ellen Best, View of the Italian room at the Städelsches Kunstinstitut (detail), 1835, water- and bodycolours, Photo: Archive of the Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

The leading artists

In three of the five skylight rooms, the lower sections of the vaults were decorated with portraits of important artists: represented in the furthest skylight room with antiquities were the “representatives of Greek art and education” (Vorläufige Mittheilungen 1833, p. 8). In the Early German room, the focus lay on Albrecht Dürer and Jan van Eyck, who were surrounded by other painters, sculptors and architects. In the Italian room, this role was given to Raphael and Michelangelo, whose portraits were depicted above the end wall, where the bust of the institute’s founder was placed.

The devaluation of the Dutch and Flemish

It is telling that the Dutch and Flemish room was not decorated with portrait medallions. Its decorative programme subsumed Dutch and Flemish painting under “the style of the later Middle Ages” in which nature was merely copied and Italian art was imitated (Vorläufige Mittheilungen 1833, p. 9).

Sources

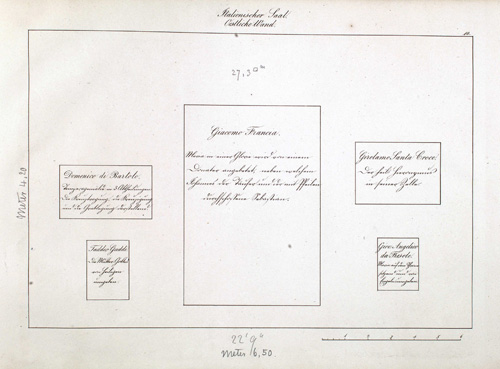

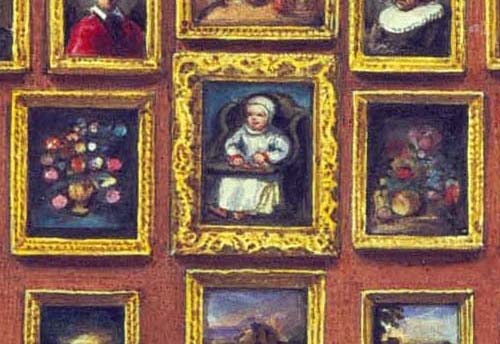

Hanging plans and detailed views

Thanks to printed hanging plans, we are well informed about the gallery’s presentation at the time of its opening on 15 March 1833. That rapid changes took place soon afterwards, especially in the Italian room, is known thanks to representations of the gallery by the English watercolourist Mary Ellen Best, which she had made during her stay in Frankfurt in 1835. These provide a good impression of the rich decoration and the wall colours of the rooms. That same year, the new “Verzeichniss der öffentlich ausgestellten Kunstgegenstände” (“Directory of the Publicly Exhibited Art Objects”) was published. The order of this directory followed that of the rooms. A comparison with the hanging plans enables us to come to some interesting conclusions regarding the system according to which the paintings were hung. It also provides us with the opportunity to reconstruct the parts of the heavily-altered Italian room not captured by Mary Ellen Best in 1835.

Frames

The frames were an important part of the presentation. Mary Ellen Best’s watercolour of the Dutch and Flemish room shows how a broad, splendidly decorated frame could set a central painting apart from its surroundings. It would have been too costly, however, to reconstruct the surviving historical frame in the 3D model. For data-economic reasons, we have limited ourselves to frames with straight borders. The basis was formed by photos of 25 historical frames from the collection of the Städel Museum. Our goal was to convey a varied impression. All of the unknown or non-extant paintings have been represented with a generalised frame.