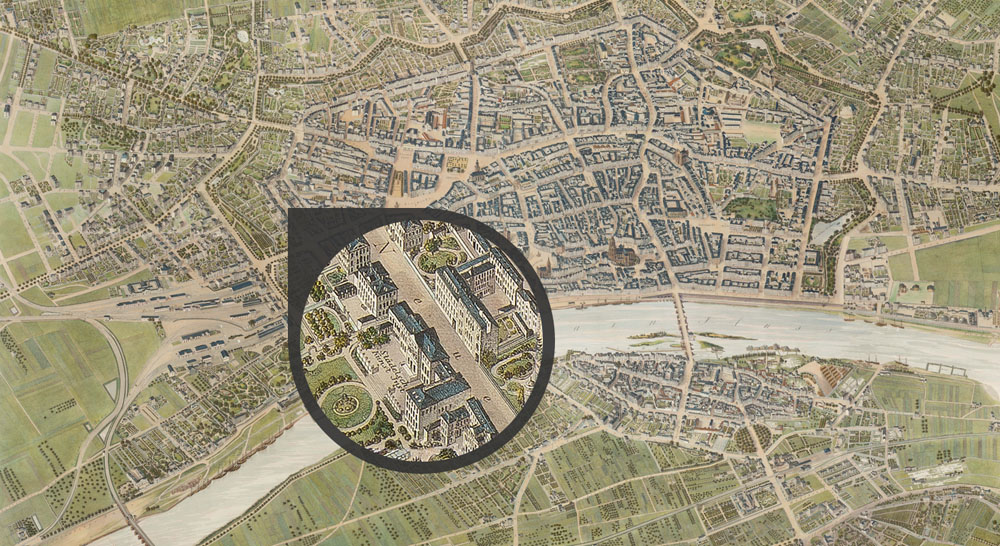

1833

Neue Mainzer Strasse

“[…] in one of the most beautiful quarters, near the public walkways.”

In March of 1833, the Städelsches Kunstinstitut (“Städel Art Institute”) moved to the Neue Mainzer Strasse. The new location was not far removed from the Rossmarkt and the city centre, yet nevertheless relatively out in the open. The property bordered on the “Anlagenring”, which had only recently been created over the city’s demolished medieval ramparts.

History

The Städel Board’s first job offer of 1818 Overbeck never received. The second, in 1823, he declined. Although the Nazarene delivered the painting, which had been ordered in 1829, only in 1840, it reflects the spirit in which the Städel was established at the Neue Mainzer Strasse in 1833. From the outset, Overbeck’s work had been intended to represent the conclusion and culmination of German contemporary art.

The Städel as “art university”

Up until 1828, the art institute’s activities had largely been dormant due to a multi-year inheritance dispute with distant relatives of the founder. The legal struggles came to an end through a costly settlement. Shortly afterwards, the Vrints-von-Treuenfeld Palace at the Neue Mainzer Strasse, named after its previous owner, was bought. After some remodeling it was meant to unite the art collections and an art school under one roof. For this purpose, the Board made a number of important personnel decisions and created favourable conditions for the realisation of the ideals of the artist group of the Nazarenes: an artistic training of a new kind.

In the first years after Städel’s death, an attempt was made to make do with the house at the Rossmarkt. In order to integrate newly acquired works, building sections were added and the hanging of the paintings was altered. In 1822/23, the composition of the Board was changed as well: because Johann Friedrich Böhmer (1795-1863), a librarian and Frankfurt’s city archivist, as well as the cloth merchant and art patron Philipp Jacob Passavant (1782-1856) were added, the so-called “Good Cause” gained the upper hand. With this phrase, Böhmer referred to the artistic ideal of the Nazarenes, active in Rome. This group of artists strove for a revival of German art inspired by the example of the (Catholic) art of Renaissance Italy, which was personified by Raphael. To this end, Städel’s goal for his art institute and collection to serve the training of young artists (both male and female!), as stipulated in the foundation charter, seemed to fit perfectly.

The cousin of new administrator Philipp Jacob Passavant, the artist and budding art historian Johann David Passavant (1787-1861), already gave advice behind the scenes. It was originally his idea to bring in Philipp Veit (1793-1877) and Friedrich Maximilian Hessemer (1800-1860) as Professors of respectively Painting and Architecture. While Veit also became the institute’s director, Hessemer was responsible for the modification of the newly acquired Vrints-von-Treuenfeld Palace at the Neue Mainzer Strasse.

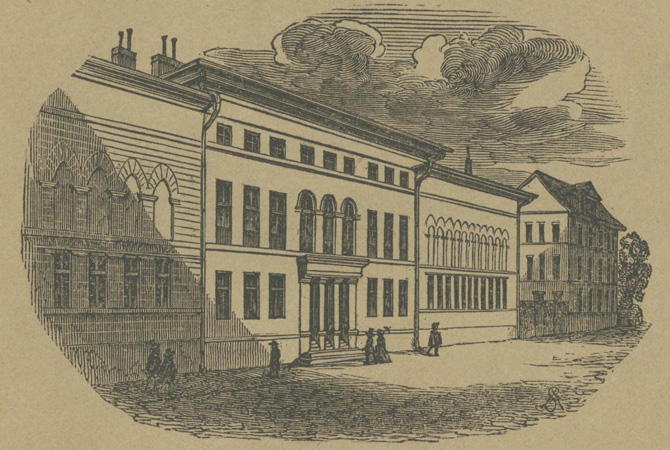

Architecture

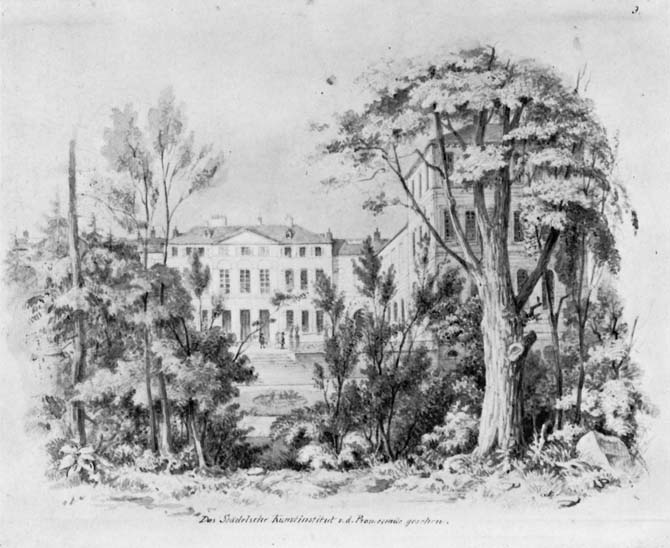

The modification of the postmaster’s villa

Carl Vrints von Treuenfeld (1765-1853), Upper Postmaster of the postal service of the House of Thurn und Taxis, sold his townhouse to the Städelsches Kunstinstitut in 1829. The classicist villa at Neue Mainzer Strasse 47-51 had been constructed ten years earlier by Johann Friedrich Christian Hess (1785-1845), who would later become Frankfurt’s city architect. The modifications, made by Hess himself and by Friedrich Maximilian Hessemer, concerned both the façade and the house’s internal structure.

The house’s façade was inspired by Italian Renaissance designs. The reliefs of the rustications and arcade arches remained rather flat, so that “the longitudinal walls without windows” would deviate from what was seen elsewhere in Frankfurt (Kunst-Blatt 1834, p. 73). Already from the outside, one could see that the main building was divided into three sections. The entrance was placed in the centre. From there, one could go to the studios of Professors Zwerger and Hessemer, presumably located in the right section of the ground floor. Further classrooms and offices, as well as the hall used for figure drawing, were located on the ground floor as well. Behind the left wing, a transversely oriented section was added, the back of which housed the studio of Philipp Veit.

The visitor reached the first floor via the main staircase in the centre of the building. Here the art collections were housed. In the centre were the three “reception rooms” with windows, above which, on the second floor, the director’s apartment was located. Adjacent to these on both sides were the large rooms with paintings and antiquities. As classic skylight rooms, these spaces received their light solely from above. Initially, in the southern wing facing the garden only smaller rooms with floor to ceiling windows (to receive northern or southern light) were planned. It was not until Johann David Passavant’s directorship that another skylight room was established, by opening up the wing’s first two rooms into one space.

Opening Hours

The Städelsches Kunstinstitut was inaugurated on 15 March 1833, the eighteenth anniversary of the founder’s third and last will. The public was able to visit the collection rooms from 17 March, a Sunday, on. According to the “Verzeichniss der öffentlich ausgestellten Kunst-Gegenstände” (“The Directory of Publicly Exhibited Art Objects”) of 1844, a visit was possible on all days, except Saturdays, from 10:30 until 13:00 – free of charge. For “travellers, who are only passing through”, it was also possible to visit the collection on Saturdays, presumably for a fee (Directory of 1844).

The library was open on Tuesdays and Thursdays from 10:00 until 13:00. On winter evenings, viewings of engravings were organised for small groups. Those who wanted to view a specific drawing or print could make an appointment with the director.