1878

Schaumainkai

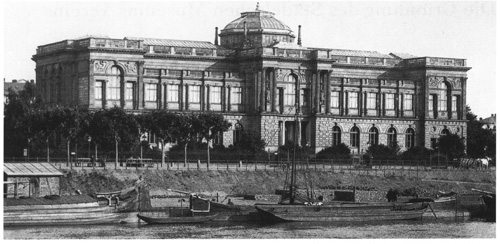

On 13 November 1878, the Städel Museum’s new building at the Schaumainkai was opened. The building for the art school at the new location had already become operational the year before. The relocation to Sachsenhausen, on the opposite bank of the Main river, was controversial due to its considerable distance from the city centre.

“[…] it was not possible to be fully joyful […] Everyone would have been happy, if the collection had stayed at its old location.”

History

A new building in Sachsenhausen

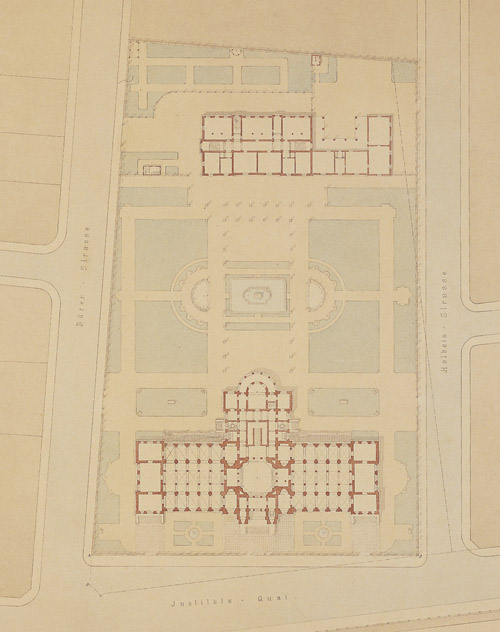

Already in 1850 there had been plans to expand the Städelsches Kunstinstitut at the Neue Mainzer Strasse. A lack of funds, as well as the wars of 1866 and 1870/71, prevented a relocation to a new building at the Bockenheimer Landstrasse. There, the former “Leerse’sche Garden” west of the Unterlindau had been bought by the Städel Board and temporarily rented to the Zoo. The profitable sale of this property finally made it possible to realise a lavish new construction project at the museum’s present location: a grand and prestigious museum building, as well as a separate building for the art school. This was only possible on an extensive piece of land, cheaply bought from the city, on the bank of the Main river in Sachsenhausen, outside the then city limits.

“This location offered the advantage of good light.”

The relocation of the Städelsches Kunstinstitut to Frankfurt-Sachsenhausen was part of a programmatic city development that is only comparable to the recent move of the European Central Bank to Frankfurt-Ostend. The houses on the surrounding streets would only be built during the subsequent decades.

The organiser

“on 13 September [1878], the director and caretaker spent the night in the new building for the first time.”

An important organiser of the relocation was director Gerhard Malß (1819-1885). The painter of architecture pieces and landscapes, well acquainted with Philipp Veit and partially trained at the Art Institute, had been working at the museum since 1849. As Johann David Passavant’s assistant, he had initially been responsible for the cataloguing and reorganising of the graphic collection. Even today, his handwriting on folders, boxes and passe-partouts testify to his work. After Passavant’s death, Malß was appointed director in 1862 (Board report 1863, p. 11f., Board report 1888, p. 19). Malß must have had a significant impact on the museum’s refurbishment at the Schaumainkai. His plans for the furnishing of the print room and the library, as well for the installation of parts of the plaster cast collection have survived. The hanging plans for the painting gallery are by his hand as well. They form the basis for our reconstruction.

Architecture

A Temple for the Arts

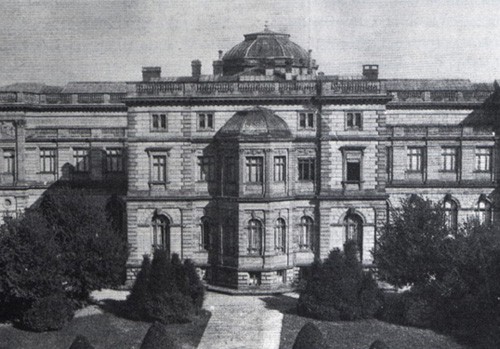

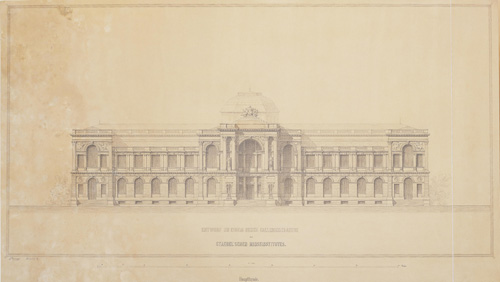

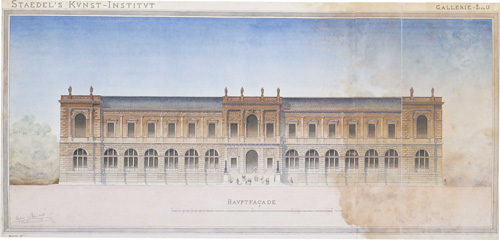

The new museum building was designed by Oskar Sommer (1840-1894), the architecture teacher at the Städelsches Kunstinstitut. He used stylistic elements of Italian High Renaissance architecture and was also inspired by Semper’s recently constructed Gallery in Dresden. Today’s “Main wing” of the Städel Museum was a freestanding palace-like structure. An avant-corps with entrance steps and a rotunda emphasised the building’s centre. Already from the exterior, one could recognise the interior structure of the wings: elongated halls were accompanied by smaller, transversal rooms. Corner risalits closed the building on both sides. While the large halls on the upper floor were lighted through skylights, the smaller cabinets on the street- and garden sides used sidelight.

Competitive designs

After an initial, unsuccessful nationwide call for proposals in 1873, the Frankfurt architects Carl Jonas Mylius (1839-1883) and A. Friedrich Bluntschli (19842-1930), as well as Oskar Sommer, were asked to submit plans for the museum and art school. The basic structures of both museum designs resemble each other, testifying to the Board’s strict specifications. Both designs, however, also share the influence of a great model: the Dresden Painting Gallery of their shared Zürich teacher Gottfried Semper (1803-1879). In the end, Sommer’s designs were realised with a few modifications. They are characterised by a stronger sculptural structuring of the façade, as well as an emphasised dome.

National heroes

Up to this day, Albrecht Dürer and Hans Holbein greet the visitors from the façade, on both sides of the main entrance. At the end of the nineteenth century, they were regarded as the “main representatives of German painting” (Board report 1879, p. 40). With these two larger-than-life statues by August von Nordheim (1813-1884), the museum’s new mission statement was presented already at the entrance. The statues were accompanied by two allegorical reliefs: a young woman with a lyre representing Poetry, and a second, older woman with a long scroll personifying History. The two concepts constituted the foundations of (history) painting.

The shift towards a purely German juxtaposition was significant. At the old museum at the Neue Mainzer Strasse, the Italian-German pairing of Raphael and Dürer had set the tone since 1833. However, in a time of strenghtened national self-awareness following the proclamation of the German Empire in 1871, views on the history of art had changed. Although the style of the museum’s architecture was still inspired by the Italian Renaissance, German role models now sufficed. The Institute not only possessed three paintings by Dürer (inv.-no. 874, 890, 937), but also a rich collection of his prints. The collection of works by Holbein had only recently been expanded with the “Portrait of Simon George of Cornwall” (inv.-no. 1065). That these paintings were the first to be moved to the new building was surely no coincidence.

Virtues on the building

Fire safety precautions were used as arguments for the separation of the collection rooms and the art school. Yet, in actuality this decision was the result of a programmatic shift. For the first time, the Städelsches Kunstinstitut presented itself as a self-assured art museum. Only the decoration of the museum building referred to the academy, which now – in a literal sense – was placed in the background.

Each spandrel of the corner risalits was decorated with two allegorical figures. The reliefs above the windows on the first floor showed the Virtues essential for the creation of art: visible on the main façade were Love and Diligence to the west (right), and Beauty and Truth to the east (left). On the back side of the building, the allusions to the Städel School were more obvious: here, Study and Cheerfulness decorated the eastern risalit. The only reliefs to have been preserved in their entirety are Power and Temperance on the back of the western risalit.

The pictorial programme was conceived by Gustav Kaupert (1819-1897), professor at the Städel School, who executed it together with three other local sculptures – all former Städel students.

Opening Hours

The opening hours at the Schaumainkai were only expanded slightly compared to those of the mid-century. The gallery was usually open to the public from 11.00 until 14.00 – on Sundays only until 13.00, but on Wednesdays until 16.00. The print room and libraries had different opening hours: they could be visited Mondays and Thursdays between 11.00 and 13.00, and on Tuesdays and Fridays between 11.00 and 13.00, as well as between 16.00 and 18.00.

“The institution is closed on all major holidays.”