1878 Northeastern corner room

Raphael

and the Nazarenes

The central reception rooms at the Neue Mainzer Strasse had been decorated with a room overview, two depictions of doors, and a total of 13 images of domes and 26 of pilaster ornaments - all from Raphael’s Loggias at the Vatican. The same series was displayed in a similarly programmatic manner at the new building at the Schaumainkai. Here, however, they were combined with frescos by the Nazarenes, the German-Roman group of artists from the first half of the nineteenth century that had modelled its artistic ideals after the Italian High Renaissance. With Philipp Veit and Johann David Passavant, the Städelsches Kunstinstitut had been managed by two important figures within this movement.

The colourised, printed reproductions after Raphael decorated the two eastern corner rooms flanking the smaller skylight room with Philipp Veit’s “Christianity Introducing the Arts in Germany”. However, the interweaving of Raphael’s motifs – which did not merely serve a decorative purpose, but were mainly shown for their artistic prominence – with Nazarene art went even further: the plan was to exhibited them with cartoons, the original-sized templates for frescos. Friedrick Overbeck’s “Joseph Being Sold to the Egyptians” was presented in the southern room.

In 1818, the artist had designed this work for the Palazzo Zuccari, the house of the Prussian general consul Bartholdy in Rome (today the Bibliotheca Hertziana). The cartoon came from the estate of long-time Städel Board member Philipp Jacob Passavant. On the opposite wall, an imposing cartoon by Carl Heinrich Hermann was put on display. In 1828, the long-time assistant of Peter von Cornelius had created this scene from Bavarian history for the arcade at the Hofgarten of the Munich Residenz. Since their creation, both works had become classic examples of newer German history painting.

Basis

for the reconstruction

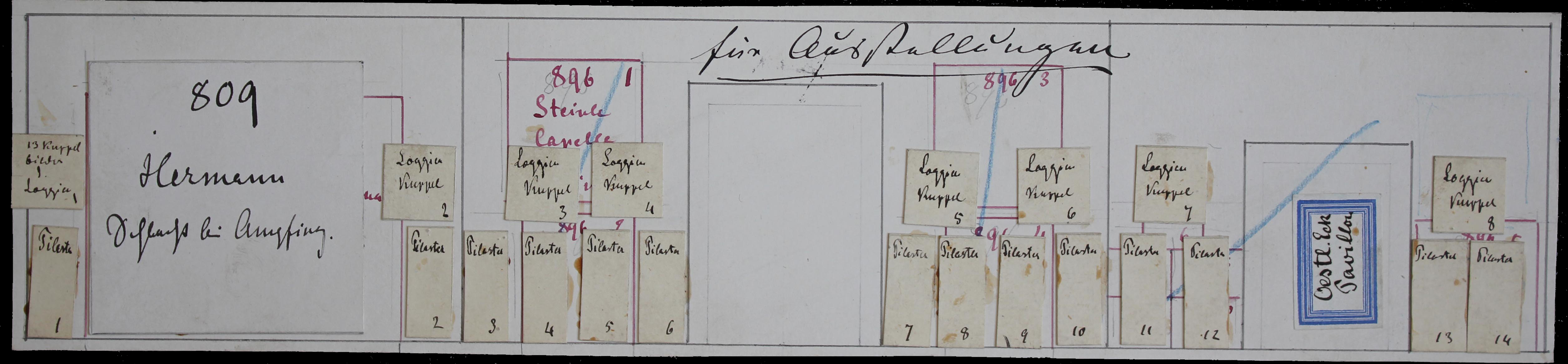

In case of the corner rooms as well, at least three planning phases can be verified. The added note “für Ausstellungen” (“for exhibitions”) on the plan of the northeastern corner room reveals that it was presumably not considered as a space for permanent presentations. Our reconstruction visualises the situation documented by the final hanging plans.

Yet, the distribution of the prints and cartoons across the corner rooms and the southern galleries cannot be fully reconciled with the Directory of 1879. In fact, in the entire museum, more works appear to have been exhibited than indicated on the preserved hanging plans for the upper floor.

The hanging plan for the northeastern corner room, for example, shows that, instead of the prints after Raphael, an exhibition of cartoons by the Städel teacher Edward von Steinle had initially been planned (inv.-no. 896 A-K). However, as Steinle’s cartoons are mentioned in the Directory of 1879 without an indication of their location, they must have been hung somewhere else. The question is, where.