1878

Schaumainkai

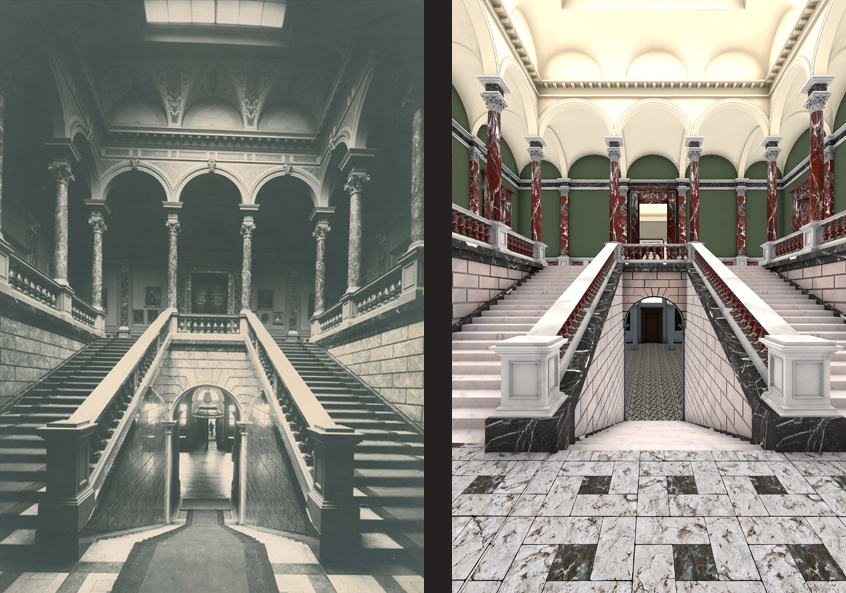

“[…] as soon as the stairs are split into two arms at the half-landing, the festive character of the column-bearing upper passage, richly executed in various kinds of marble, is expressed beautifully.”

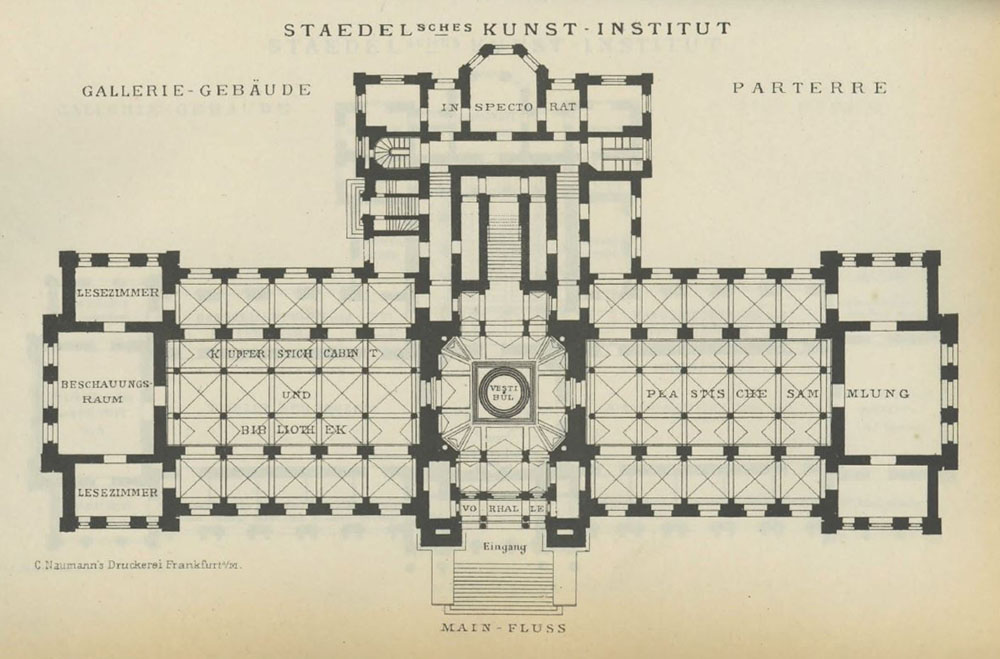

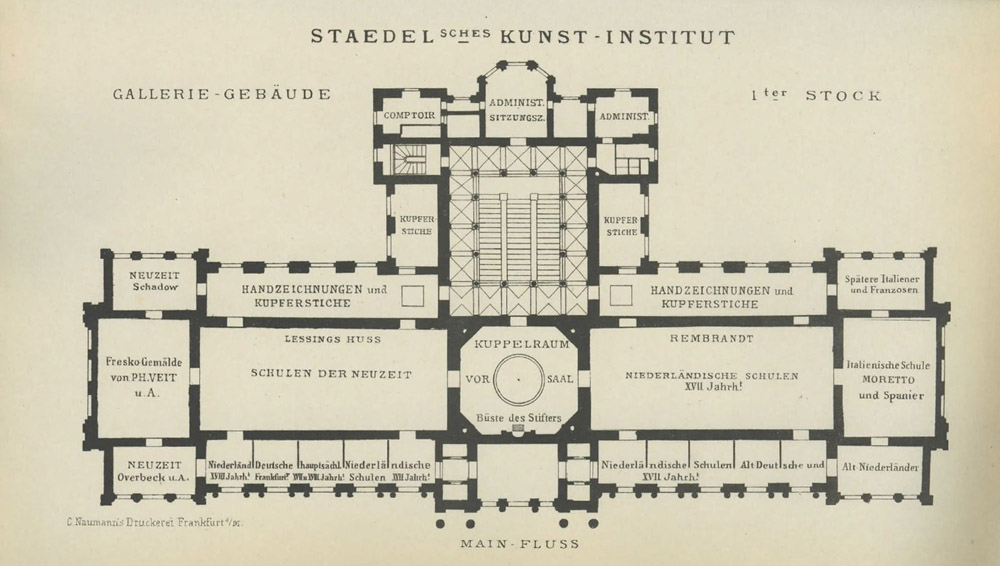

On the ground floor, the visitors could find the sculpture collection to the entrance’s right, while the print room and its library – as is still the case today – are located on the left. The entire upper floor was reserved for the painting gallery. To access it, one had to pass the stately stairwell. However, a number of structural changes to Oskar Sommer’s original design had initially made the entrance area and the first staircase appear somewhat gloomy and narrow.

A Tour

through the Museum

Ground floor

Library and print room

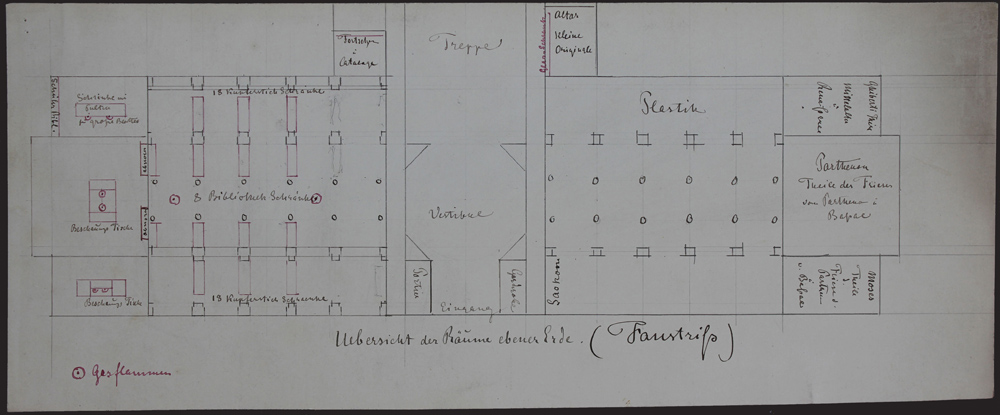

A sketch by Gerhard Malß, the director in charge, informs us about the furnishing of the ground floor. It tells us that the porter’s lodge was located to the left of the entrance, while the cloakroom could be found on the right. Placed between the columns in the large hall on the left-hand side were cabinets for books and engravings. A central aisle, through which one could access the large rooms and the two flanking small rooms, remained open. Located here were desks and exhibited prints. Light was provided by gas lights hanging from the walls and possibly also placed directly on the desks.

Sculpture collection

We know very little about the 1878 exhibition “Plastische Sammlung” (“Sculpture Collection”). Exhibited in the three rooms in the back were the casts of the frieze of the Temple of Apollo at Bassae and of the Parthenon frieze, presumably accompanied by other casts of the Parthenon. They were displayed together with casts of the most prominent works of the Italian Renaissance. Placed in the smaller room to the right was Michelangelo’s “Moses” for the tomb of Julius II, while in the left room the “Gates of Paradise”, created by Lorenzo Ghiberti for the Florentine Baptistery, was exhibited together with other modern works.

With rows of pillars and columns, the main hall was structured like a basilica. This appears to have been the main room for casts of antique sculptures. The hall’s structure, with its adjoining smaller rooms, only offered two spacious viewing axes: placed in the northern aisle, in a rather odd-looking corner, was the “Laocoön Group”. From there one could see one of the few original works; the monumental “Altar of the Virgin of Mercy” by Giorgio Andreoli (inv.-no. St.P77, Liebieghaus Skulpturensammlung, Frankfurt am Main) was housed in a “side chapel” next to the stairwell (the present cloakroom). This work had already been acquired by the Städelsches Kunstinstitut in 1835 and was placed in the room featuring Philipp Veit’s fresco of “Christianity Introducing the Arts in Germany”.

The art-historically ambitious Frankfurt school teacher Veit Valentin criticised the sculpture collection as the weakest part of the new museum. It did not offer a comprehensive overview of the history of the art form (“No trace of Egyptian, Assyrian works, of Archaic Greek works there is nothing!”). Important single works were absent, yet the worst element was the lighting:

“The light enters the main hall through two rows of windows, one on the northern side and one on the southern. There is nothing else to do but sacrifice the lovely impression of the great hall and add one or two walls […]”

The collection of plaster casts of antique and – to a much lesser extent – Gothic and Renaissance sculptures had been systematically assembled from 1817 on. The reproductions, mainly ordered in Paris and London, were considered to be equal to the collection of original paintings and prints. Thus, the collection of casts did not occupy a place of equal rank as the painting gallery only at the Neue Mainzer Strasse, but also after the museum moved to its present location at the Schaumainkai.

Only in 1907, the casts were removed by the then director of the Städel Museum, Georg Swarzenski (1876-1957). Following the spirit of the times, he considered them to be nothing more than “art-scholarly study objects” that in no way were comparable to originals. The plaster casts were first put into storage and subsequently moved to Frankfurt University, founded in 1914. There they became part of the study collection of the Archaeological Institute. Except for the casts of the Parthenon frieze of the Acropolis, which had been firmly walled into the Institute’s former rooms in the Jügelhaus, the University’s original main building, all casts were destroyed in 1944 during the bombings of World War II.

Upper floor

Rotunda

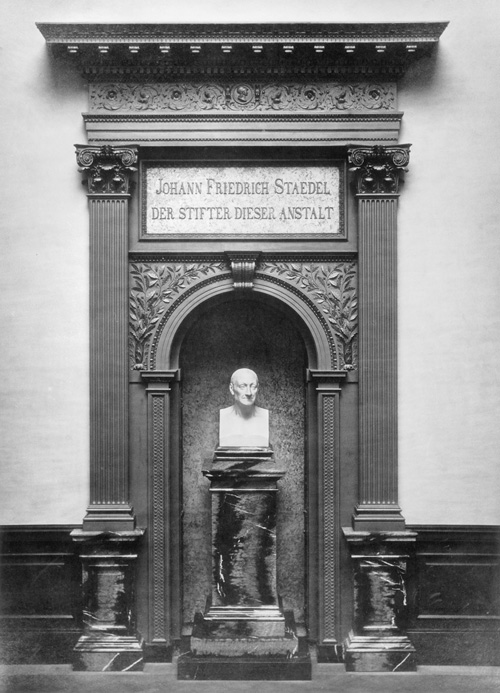

Coming from the stairwell, which was decorated with differently coloured marble, visitors first reached the octagonal rotunda. It was described in a positive sense as being “colourless” (Sommer 1879, p. 41) and was dedicated to the “founder of this institution”, Johann Friedrich Städel.

At the end wall, Städel’s bust, created half a century earlier, stood in a niche in front of a triumphal arch. The latter was presumably made out of dark nutwood. The balustrade around the central opening in the floor, which offered a view from the vestibule on the ground floor up to the dome, was likely designed in a similar style. It presumably shared the room’s octagonal shape and consisted of nutwood with bronze inlays showing “the Städel coat of arms, from which sprout tendrils with cornucopias, repeated four times” (Sommer 1879, p. 41).

At the time of the opening, the rotunda was “temporarily furnished with casts of famous marble works […]” (Valentin 1879, p. 119), yet which casts cannot be established with certainty. Among these works may have been eight of the collection’s nine portrait busts of mainly Roman emperors, as they would have excellently framed Zwerger’s bust of Städel.

Painting gallery

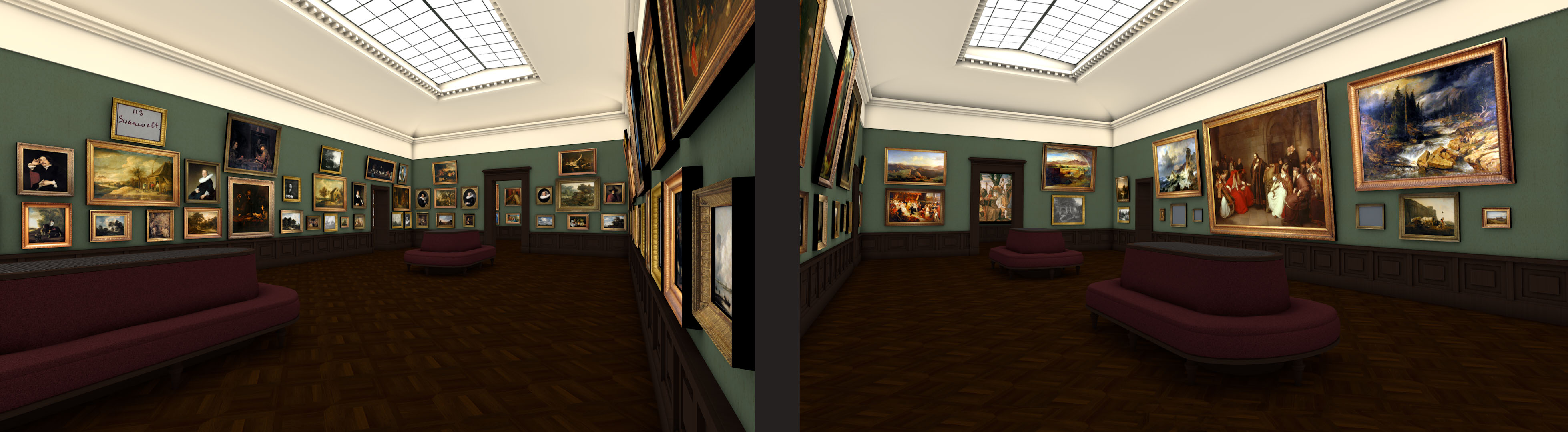

From the rotunda, one had access to the main skylight rooms. On the right, contemporary, nineteenth-century paintings were exhibited, while their art historical models were presented on the left. Despite this spatial separation, it is possible to identify conceptual connections between the two wings.

The juxtaposition of past and present is all the more remarkable, as the main floor of Semper’s Dresden Painting Gallery, which had been the great model for Sommer’s museum building in Frankfurt, was dedicated solely to Old Masters. In Dresden, the Italian and Netherlandish schools were placed opposite each other, while the weaker paintings and works of the nineteenth century were shown on the second floor. In comparison, the programmatic link between contemporary and Old Master art is a special feature of the Städelsches Kunstinstitut. It grew out of the close connection between the collection and the art school, thereby fulfilling a fundamental mission stipulated by Städel in his foundation charter.

“The paintings themselves have been presented in an exemplary manner by the director, Mr G. Malß. Not only has the […] necessary historical arrangement been taken into account as much as possible, the even more difficult aim has also been accomplished, that is to hang the paintings in such a manner within this context, that the one hurts the other as little as possible.”

The skylight rooms on both sides of the rotunda were programmatically interrelated.

The transverse skylight room at the end of the eastern side was occupied by Philipp Veit’s “Introduction of the Arts in Germany”. An Italian specialist had managed to remove the fresco from the wall at the abandoned museum building at the Neue Mainzer Strasse, so that already during the summer of 1877 it “was brought to Sachsenhausen on the shoulders of two porters” (Kaulen 1878). From 1878, the architectural pendant to this “Veit room” would be the room with mainly Italian paintings, among which was the large altarpiece by Moretto da Brescia (inv.-no. 916), prominently placed at the end of the viewing axis. However, the two largest skylight rooms were interlocked as well: most prominently displayed in the Dutch and Flemish room were history paintings by Rembrandt and his school. Its counterpart was called the “Hus room”, after Carl Friedrich Lessing’s painting. Just as Dutch and Flemish art was distinguished from Italian painting, Lessing and other representatives of the Düsseldorf School had developed a counterpoint to the artistic ideal of the Nazarenes, for example by taking inspiration from the art of the Dutch “Golden Age”. That the masterpieces of Dutch and Flemish paintings were assigned the largest of the Old Masters rooms was not only the result of their quantitative dominance, rooted in the collection’s origins; due to recent artistic developments, the art historical field was in the process of re-evaluating Dutch genre painting as well.

Experienced

art history

The entanglement of Italia and Germania

The strict chronological division of the wings was abandoned in two places: all of the cabinets on the northern side of the building, facing the Main, showed paintings from the sixteenth to eighteenth century. However, exhibited in the two side galleries on the opposite garden side were nineteenth-century cartoons, mainly by Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld and Philipp Veit. Fifty years after their creation, they had already become part of the “canon”. The manner in which they were exhibited once again constituted a realisation of the Nazarene ambition to learn from the excellence of the Italian masters: the cartoons were presented together with reproductions of works by the Renaissance masters Raphael and Titian.

Artistic continuity

Not only were the main skylight rooms interrelated, a tour through the side rooms repeatedly offered visitors the opportunity to discover interrelations here as well. The view from the southwestern gallery into the adjacent corner room offers a good example of this perception of continuity. Although the engravings after Raphaels Stanze, the cartoons by Schnorr von Carolsfeld, and Pompeo Batonis “Allegory of the Arts” represented different periods, they were connected through a common artistic ideal: figurative history painting. This type of painting still determined the guiding principle of the art school in 1878 – at a time when for example in France, Impressionist painters were already celebrating their first successes.

With the statues at the main entrance, the shift in artistic models had already become visible on the building’s exterior – from the pairing of Raphael and Dürer, following Nazarene ideals, to Dürer and Hans Holbein the Younger. These latter artists represented a German national art, of which the Städel art school considered itself an heir as well. At the same time, it was inconceivable to think of art without the influence of Raphael, the main representative of the Italian Renaissance. Nevertheless, especially under director Johann David Passavant the collection of Early Netherlandish and German painting had been expanded, with works by Jan van Eyck up to to Holbein. Visitors could experience this key area of the collection in the northwestern building section. Located next to the main Italian room, it supplemented but did not supplant it.

Sources

Architecture and interior

Oskar Sommer’s building still exists: known as the Städel Museum’s “Main wing”, it today houses the Department of Prints and Drawings, the library and the bookshop on the ground floor, while the collection of Old Master paintings is located on its upper floor. Damage caused during the war was mainly limited to the corner risalits, which were restored after 1945 in a more modest fashion. As part of the post-war renovation, the stairwell in particular was refashioned in a more modern style. For the reconstruction in the 3D model, we were able to use a series of photographs of around 1920, contemporaneous descriptions, as well as architectural plans.

Room division

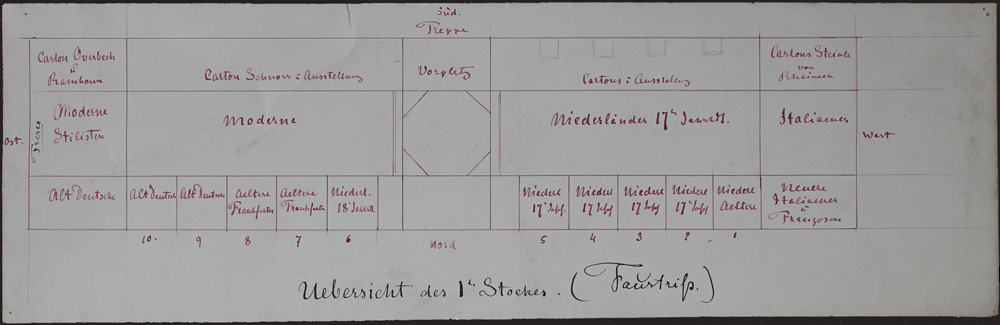

The substantive division of the skylight rooms appears to have been fixed from the outset. However, the assignment of the side cabinets and the corner rooms appears to have led to longer discussions.

The initial plan for the eastern skylight room shows that director Gerhard Malß first intended to combine Philipp Veit’s fresco with Early German and Netherlandish paintings. This explains why a rough sketch places the Early German rooms on the eastern side, which would have caused a striking discontinuity in relation to the other cabinets. The final decision to present the Early German (and Early Netherlandish) paintings in the chronologically correct northwestern corner room, thus shifting the sequence of the cabinets from left to right, had additional consequences. The Italian and French paintings of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, for example, moved from the originally planned northwestern to the southwestern corner room. Consequently, the initial idea to reserve the northern, Main-facing side exclusively to history paintings and show contemporary works on the garden side, had to be abandoned. This we know because the floor plan in the “Directory of Publicly Exhibited Art Objects of the Städelsches Kunstinstitut” of 1879 includes room names.

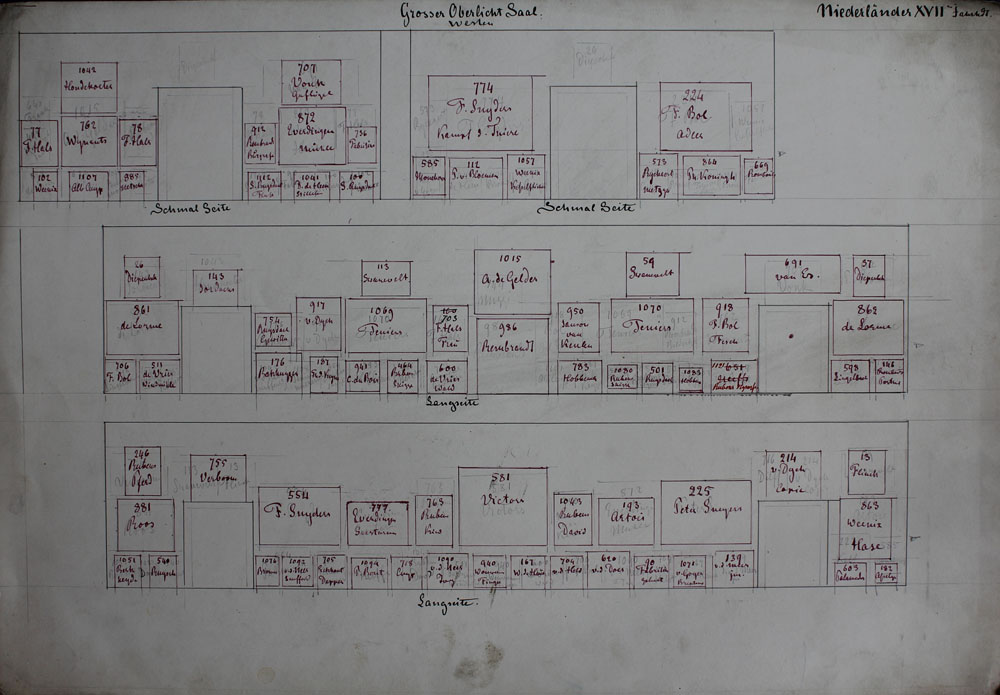

Hanging

Director Gerhard Malß had planned the hanging of the painting gallery with help of hand-drawn wall plans. Yet, although he identified each respective room on the plan, he did not specify the walls of each room.

For the allocation, therefore, additional sources, such as the floor plan in the Directory of 1879, had to be used. An additional challenge was caused by Malß’s inaccurate representation of the architecture. The director appears to have drawn the cabinets in sequence, yet without paying attention to the arrangement of the passageways and the varying measurements of the doors. If the preserved hanging plans accurately reflect the final planned design, some changes must have occurred when Malß oversaw the installation between 3 August and 7 October 1878.

The documents hint at two to three different planning phases. The designs were drawn with pencil and subsequently altered with violet and black, yet also with red ink. Some plans additionally feature deletions and pastings. The most drastic conceptual changes mainly concerned the contemporary paintings. The final addition was the “Venus” by Cranach the Elder, which had been donated to the Städel by Board member Moritz Gontard on 31 July 1878. A comparison with the “Directory of Publicly Exhibited Art Objects of the Städelsches Kunstinstitut”, published one year after the opening, presumably during the second half of 1879, confirms that the plans drawn in violet must have been executed by and large. It mentions a few additional paintings, some of which only came to the museum after its opening. However, it lacks 21 works included in the hanging plans. Among these are 15 works that were sold in May of 1882. It is likely that these paintings were sorted out either during the installation or, less likely, shortly after the opening. With the exception of cabinets 5 and 6, as well as the small eastern skylight room, the changes affected all the rooms. However, in most rooms only one image was removed, while in cabinets 7 and 9, this applied to respectively three and four paintings. As the Directory was now sorted according to art-historical criteria and no longer according to the gallery hanging, this source unfortunately did not help with eliminating some last ambiguities. We have therefore decided to reconstruct the presentation as written down in the final hanging plans. We are aware of the fact that not every single detail reflects the situation of October 1878, yet the overall reconstruction nevertheless provides a reliable impression; specific problems are mentioned on the pages discussing the single rooms.

Frames

The paintings’ frames were likely much more opulent than shown here in the reconstruction. Not only were some works restored in preparation for the relocation to the Schaumainkai, it is also possible that paintings received new frames. This is at least suggested by the fact that, at the Städel Museum, a number of frames with elaborate historicist designs and decorations have been preserved. Deviations in the reconstruction result from labour- and data-economic factors. Our goal was to provide a varied appearance in the 3D model. The stocks from the Städel Museum’s frame storage could in fact partially be assigned to specific paintings. However, in many cases we selected a fitting frame from a collection of 25 photos. All of the unknown or non-extant paintings have been represented with a generalised frame.