1816

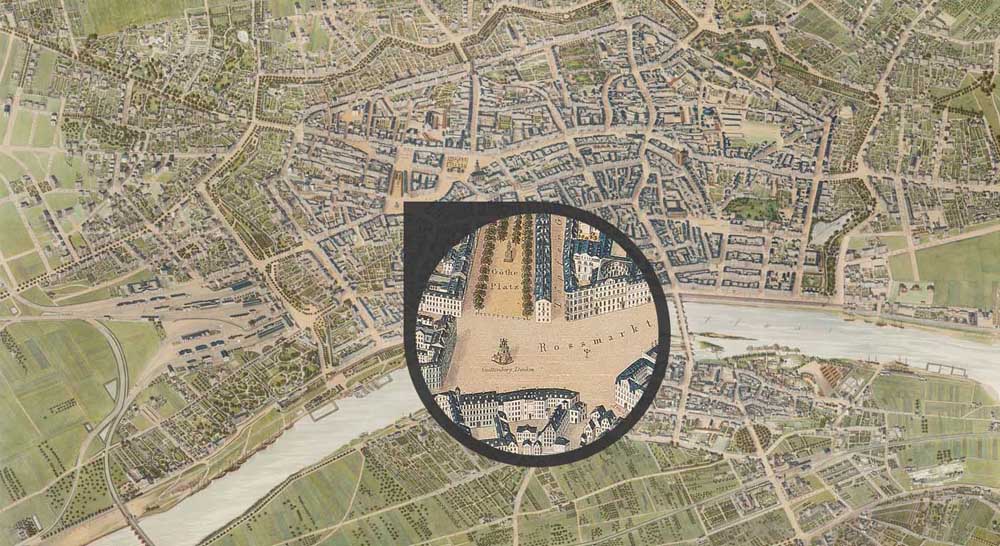

Rossmarkt

“Ever since my youth, I have nourished a passion for paintings, engravings and other artistic things”

(Whereabouts of the original document unknown)

Johann Friedrich Städel died on 2 December 1816. To the “Städelsches Kunstinstitut” (“Städel Art Institute”) he bequeathed his art collection, his fortune, as well as his landmark house at the Rossmarkt. The latter he had acquired in 1780 and modified in 1785. The spice merchant and banker had accumulated his art collection over a period of half a century.

History

The trade city of Frankfurt

During the eighteenth century, Frankfurt was a city of bustling trade and successful business. The conspicuous wealth of its citizens

was seen by their contemporaries with astonishment.

“The stores here offer such a tasteful appearance, the goods on display are so precious that you could hardly see anything more appealing in Paris.”

(Strombeck 1838, p. 331)

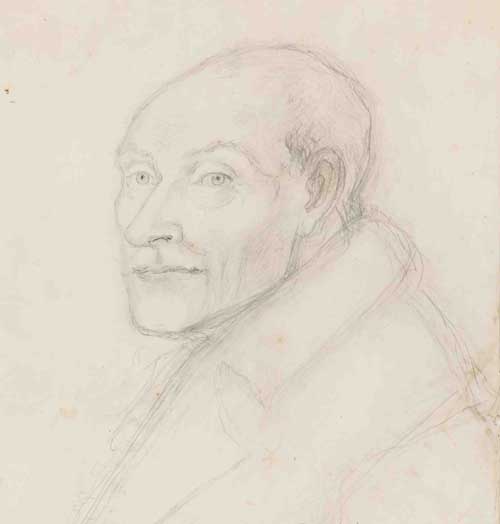

Johann Friedrich Städel

One of these Frankfurt merchants offering goods from all over the world was Johann Friedrich Städel (1728-1816). He obtained his goods, such as coffee from Java or the pigment indigo from overseas via Amsterdam and negotiated major loans all over Europe.

With all his financial success, Johann Friedrich Städel kept a sense of justness and usually signed his letters cheerfully with “with the best of regards”. To his contemporaries, his worldview and the extent of his wealth only became clear after his death, with the creation of the Städel Foundation, which still exists today.

Städel appears to have lived a secluded life, as a fellow-citizen from Frankfurt wrote that he was ...

“not one of those ordinary exchange creatures, who waste their spare hours with grandstanding feasts and social pageantry. In friendly silence, his mercantile ways are embellished with the fruits of art and knowledge”

(Gerning 1800, p. 29)

The Rossmarkt

When the 50-year-old merchant received a large inheritance after his parents’ death, he purchased a property at the Rossmarkt that perfectly served his needs. After the Zeil, the Rossmarkt was the most prestigious location in the city.

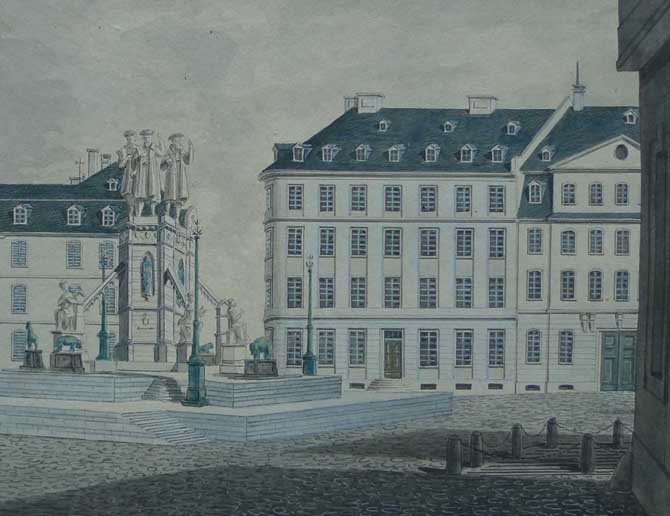

The rear buildings served as warehouses and as living quarters for the servants. At least at the time of his death, an additional building functioned as the home of Städel himself. In the front building Städel set up his office, reception rooms, and his art collection.

Städel’s house is visible in the centre, between neighbouring buildings. When looking from one of the windows of his gallery, Städel had a view of the large fountain in the foreground.

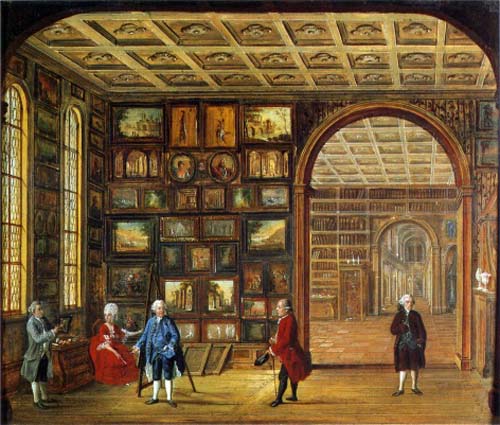

Collecting art

Collecting art was a typical pastime for wealthy Frankfurt merchants. While his colleagues had a particular interest in Dutch and Frankfurt painting, Städel’s own collection corresponded more with the taste of collectors throughout Europe: though the Dutch were dominant at the Rossmarkt as well, Städel also appreciated Italian, Flemish and German painting. French art, on the other hand, was hardly represented (though still more than among Städel’s fellow Frankfurt collectors). Städel owned works by established and recognised artists of all painting schools, among which copies of works kept in the most prestigious of European collections in Munich, Paris and London.

Architecture

A city palace

Städel’s front house featured seven window axes across three floors. The façade facing the Rossmarkt was articulated by a five-axis central avant-corps, crowned by a gabled dormer. This type of design was typical for eighteenth-century Frankfurt architecture.

The residence was similar to Goethe’s Frankfurt birthhouse. Built by Johann Caspar Goethe, this building was destroyed during the bombings of World War II, yet subsequently reconstructed. Today, it houses the Frankfurt Goethe House as part of the “Freies Deutsches Hochstift” foundation. Like Städel, Goethe’s father had opted for a type of residence that at the time was particularly appreciated among the leading Frankfurt patrician families.

Half of Städel’s house is visible on the right edge of the drawing

WAREHOUSES AND LIVING SPACES IN THE BACKYARD

Through a courtyard it was possible to enter further buildings, where Städel had accommodated his spice enterprise. Here, the storage rooms for spices, pigments, metals, sugar and coffee were located, as were the living quarters for the servants. In one of the rear houses, Städel himself lived – at least at the time of his death. At the rear, the courtyard featured a driveway connecting to the Schlesinger Gasse with coach houses for the haulers.

The commercial building and gallery

The front building was reserved for important business and Städel’s art collection. A visitor would access the house via the Rossmarkt. Greeted by a liveried servant, he would have seen Städel’s office (“Comptoir”) on the right and the small salon (“petit salon”) on the left of the entrance hall. Here, Städel conducted his business. Through the hall, one could reach the main staircase, from which it was possible to access the kitchen. The main staircase gave the visitor access to the painting gallery on the first floor.

Opening hours

“Saw also the collection of pictures of Mons. Stadle, the only one in town; it contains some tolerable pictures, and good architectural drawings.”

Johann Friedrich Städel’s painting gallery was open to anyone who was interested. Visitors – Frankfurt citizens, travelers or foreign art experts – had to register beforehand and were given a tour by the collector himself. Städel also organised evening viewings, to which he invited fellow collectors and other interested parties. In 1797, Johann Wolfgang Goethe visited Städel’s collection on three consecutive evenings. One of the last persons to be guided by Städel through his collection was Johanna Schopenhauer.

“The honourable old man received us in a most friendly manner and, despite discomforts due to his old age, personally showed us his most excellent paintings, the sight of which appeared to rejuvenate him.”

(Schopenhauer 1830, p. 34)