1816

Rossmarkt

“Multiple rooms [in Städel’s house] are decorated with exceptional paintings of all schools, while numerous cabinets contain drawings and engravings, the immense number of which, as well as their inestimable value, continue to amaze the oft-returning friends of the arts.”

(Goethe 1816, p. 62)

Johann Friedrich Städel’s painting gallery comprised of at least eight rooms. In his “dwelling”, as he in 1812 ironically described his stately residential, commercial, and collection building at the Frankfurt Rossmarkt, “… all expendable rooms were hung with paintings from top to bottom”. Books and works on paper were kept in additional rooms.

Städel presented his large collection of 476 paintings exclusively in the front building. 307 works were on display in five rooms on the first floor, while 118 further pictures hung in two rooms on the second floor. On the ground floor he showed 36 works in the small salon. In addition to that, Städel stored a number of paintings separately. All of this was far from customary: during the eighteenth century, Frankfurt collectors generally needed one or perhaps two rooms for their paintings. Only few, such as the Gogel family, had more picture rooms. Of their house, “Golden Chain” at the Rossmarkt, four rooms were reserved for their art.

The first floor

The reconstruction of Städel’s house is based on preliminary considerations by Corina Meyer (Meyer 2013). However, the digital reconstruction of the house, realised for the first time as part of the “Time Machine”, has led to a series of new insights regarding the floor plan and the allocation of the rooms.

A tour

through Johann Friedrich Städel’s painting gallery

The visitor would have been greeted by the collector on the ground floor, and followed him up the stairs. Through a large double door they would have reached the first floor, the gallery's main floor, standing first in the vestibule or reception room. From there, they could have entered the three main rooms, all facing the Rossmarkt. From the “Room to the Right” one would presumably have been able to reach a servants’ staircase and possibly an additional, separate room.

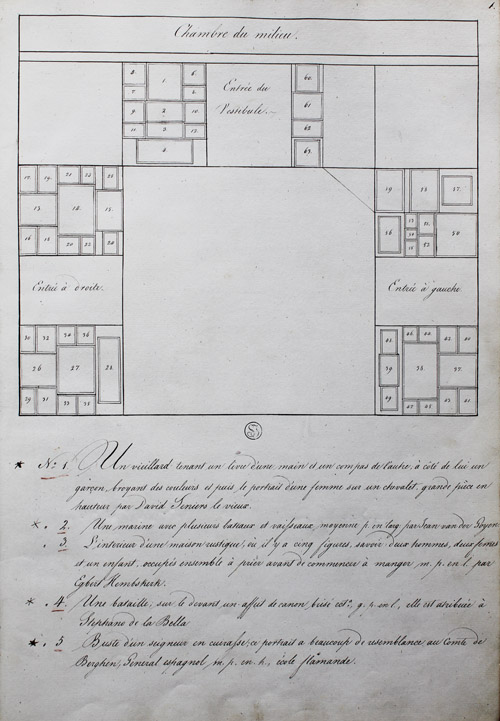

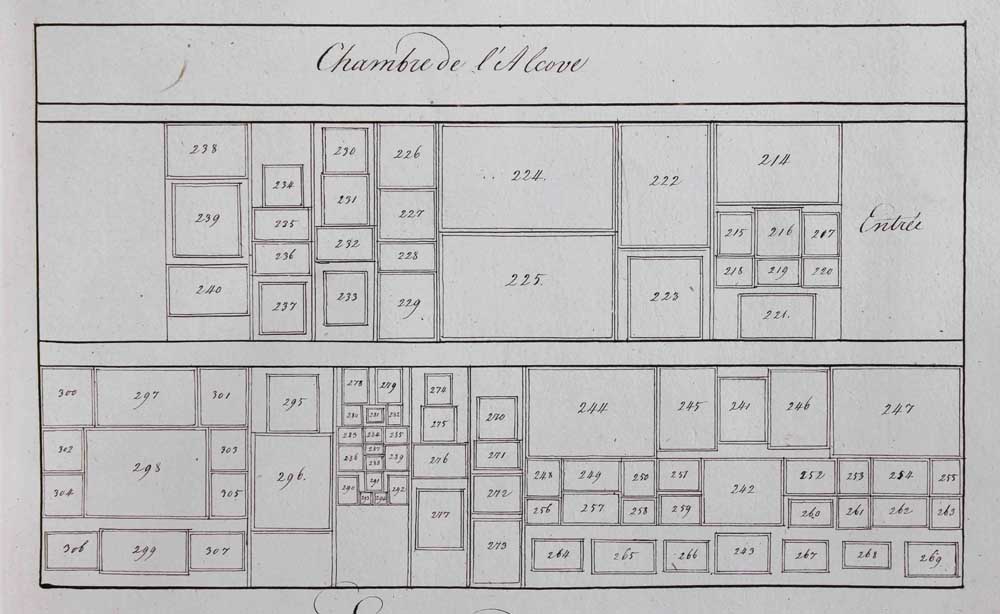

Städel’s painting inventory, the so-called Catalogue des Tableaux, written in French, alludes to a tour through the gallery. The numeration of the paintings starts in the central room facing the Rossmarkt. The so-called “Chambre du milieu” was the most prestigious room. Adjacent to this central room were two somewhat smaller rooms, the “Room to the Right” (“Chambre à droite”) and the “Room to the Left” (“Chambre à gauche”). Next, the inventory takes us back to an area called the “Chambre de l’Alcove”, which was divided in a reception room and the stairway.

The inventory subsequently suggests a continuation to the second floor. There, one would have started with a viewing of the “Chambre du milieu”, followed by the “Second Chamber to the Right” (“Seconde Chambre à droite”). A second room (to the left?) was a “Gesamtkunstwerk”. Here, Christian George Schütz had decorated all of the walls with painted landscapes and architectural motifs. As no hanging plans of these rooms have been preserved, it was not possible to reconstruct these for the “Time Machine”.

Lastly, Städel would have presented his visitors with a number of paintings which he kept separately, for example in the “petit salon” on the ground floor. These paintings enjoyed a special status. They were works with particular value to the collector, for example a copy of Correggio’s Zingarella, which was praised by Goethe and Städel kept “encaissé”, in a cassette. Städel could bring these paintings out separately and place them in the proverbial limelight.

Sales

Today, only one in six paintings from Städel’s collection has remained. In his foundation charter, Städel himself had granted the future museum’s managers, the Board, the right to trade lesser art for better pieces. This opportunity was used generously, especially in the early nineteenth century. For this reason, many of the paintings that were sold during this period cannot be identified with certainty today. For 31 of the 307 paintings on the first floor, it was possible to find substitute representations, as, during this research project, we were able to identify these works as part of other collections or find alternative versions.

Thanks to the inventory book we have a good impression of the overall presentation of the collection: by today’s standards, paintings of different geographical or historical origins were mixed in a rather diverse manner. Without a doubt, the illustrious central room featured those paintings that held a particular importance to Städel. For the most part, the rooms to the right and left respectively housed history pieces and portraits on the one side, and genre paintings and landscapes on the other. The system with which the paintings were hung on the walls, using symmetry axes, allowed for creating various correspondences and contrasts. In doing so, Johann Friedrich Städel challenged his visitors to make direct comparisons.

Sources

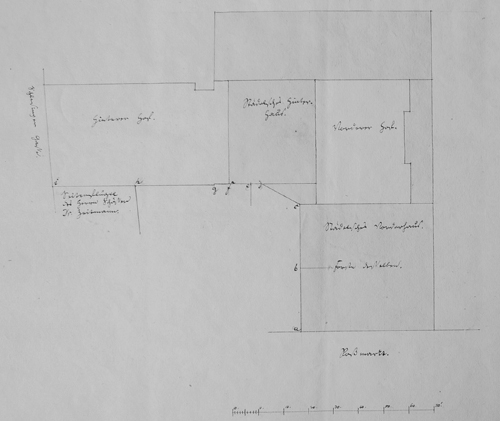

This plan shows the division of the buildings of Städel’s estate in 1832.

The reconstruction of the building

Johann Friedrich Städel’s house at the Rossmarkt was demolished around 1900. For this reason, scholars for a long time only had a vague notion of its properties. Only in 2013, art historian Corina Meyer was able to present a detailed reconstruction. Through research of construction records, order books, visual sources, and a detailed analysis of Städel’s inventory, she managed to determine the measurements and the division of the building (Meyer 2013, p. 35-62). The creation of the 3D model for this project necessitated a reconsideration of the evidence put together by Meyer. Our alternative proposals mainly concern the architecture of the rear part of the building.

A floor plan drawn in 1832 shows that, at the time, Städel’s front building facing the Rossmarkt had two annexes: on the left a passage to the rear building where Städel had his private rooms, and on the right a gallery to the skylight rooms that were built in 1818 above the former storerooms of Städel’s wholesale business. To provide access to these sections, windows would have had to have been enlarged. One of these windows might have been part of the stairway.

Corina Meyer determined that the stairway would have been located in the southwestern part of the building. According to her, it would have run parallel to the Rossmarkt – as was also the case in the contemporaneous house of Goethe’s father. Yet, although the “Goethe House” features an open staircase, the stairway in Städel’s house was evidently built in a closed space. Still, as it otherwise would have lacked a source of light, the stairway could only have been positioned across (presumably) two window axes in an east-west direction.

Städel’s inventory book

An important source for the reconstruction of Städel’s house is the inventory, which Johann Friedrich Städel’s had drawn up towards the end of his life. The author was Johann Gottfried Jäger, who had been employed as a clerk since 1808. Based on phrases such as “I have also…”, it appears that the records were either dictated or copied from Städel’s own personal notes. The carefully written book was not intended for visitors but served as an annotated directory of ownership. With regard to the posthumous Foundation, which Städel had already established in his will as early as 1793, the inventory contained the collector’s knowledge concerning the paintings, the subjects, and the artists.

On the schematic hanging plans of the three rooms facing the Rossmarkt, the three walls hung with paintings are “folded” outwards, so that one can easily imagine the wall featuring the windows. The fourth floor plan is more difficult to interpret. The title “Chambre de l’Alcove” suggests a single room, while “alcove” hints at a private space (that may have already existed before Städel’s modifications between 1780 and 1785). On the plan, the numeration of the paintings in this room starts in the upper register to the right of one of the doors (“Entrée”), incidentally clarifying the direction of reading.

It occurred to Corina Meyer that, through vertical lines, the paintings were divided into 13 sections. Well recognisable, for example, is the symmetrical structure of the tableaux on one of the longitudinal walls, or the crowded arrangement of small-sized paintings over an empty spot, presumably an open fireplace. Meyer linked these so-marked groups of paintings to subheadings in the painting list below the plan. These – such as “Entrance to the right-hand interior” (“Entrée dans l’interieur à maindroite”, Inventory of the Städel Collection, p. 22, after inv.-no. 233) – hint at two separate rooms, an antechamber and an inner “alcove”.

We as well suspect that, with the name “Chambre de l’Alcove”, Städel referred to two rooms. However, we believe that the two registers of the hanging plan each reflect one room. The long wall and the presumed inglenook provide the vertices for the second room. The width of the last division (inv.-no. 297-307) corresponds exactly with the measurements of a piece of wall between the window side and a centrally placed double door on the first floor. The empty spaces right and left of the tableaux in the first register of the hanging plan we interpret as the exact same opening, namely to the door that leads from the stairway to the larger vestibule. The assumption that Johann Friedrich Städel had hung some of his paintings in the stairway would explain the relatively limited hanging space in plan's first register. It would additionally clarify the arrangement of the large Flemish animal paintings (inv.-no. 224 and 225). In a larger room, the placement of one above the other would have been more than odd. However, for a visitor walking up the stairs, the sight would have offered an arresting prelude.

Frames

During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, it was common to provide all paintings in a single collection with identical frames. This we know, for example, from the Saxon Elector Friedrich August II or the Frankfurt master confectioner Johann Valentin Prehn (1749-1821), who personally produced frames out of Tragacanth. It was apparently also important to Johann Friedrich Städel to, through their frames, give his paintings a homogeneous character.

It is not clear when these frames, some of which are still attached to Städel’s paintings today, were produced. They are not uniform, though numerous frames have a similar appearance due to their decoration with pearl bars or relief strips. These hint at a synchronous production, possibly even in the same workshop. For the digital reconstruction of Städel’s house, we have decided to show all paintings with a uniform and clearly fictional type of frame.